Reflecting Upon the Pentomic Division Artillery

By CPT Colin Marcum

The United States Army is undergoing changes to which many within the organization find detrimental to our nation’s interests. In an effort to distance ourselves from contingency operations, like Afghanistan and Iraq, the Department of Defense (DoD) has adopted new concepts that seek to achieve our national interests through the projection of power with standoff weaponry. While budgetary concerns are being felt throughout the armed forces, these concepts have given the U.S. Air Force and Navy a certain level of preferential treatment. As a result, in order to maintain a high level of training and modernization we have undertaken a course of action to reduce our force size. After more than a decade of conflict, to be subjected to significant budgetary constraints would seem appear to cast a foreboding shadow of uncertainty as to the direction our organization is going.

This uncertainty, however, is nothing new to the Army. Conflicts to which the United States had to raise the size of the standing Army to support had invariably reduced that force at its end. The difference between the norm of force reduction and our contemporary predicament lies in the question on the purpose landpower has in the future. Civilian leadership looking at the nation’s efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq, the general malaise towards those types of large-scale contingency operations by our citizens, have created the ‘let’s not do that again’ feeling. With greater emphasis on the strategic projection of power, coupled with the desire to devoid ourselves of commitments on the ground, the Army works to find its purpose in future conflicts. This is indeed a challenging time for our organization, but is it the first? It certainly isn’t.

Before the armistice was signed signaling an end to hostilities in Korea, the DoD was already looking forward towards the next conflict. Similar to the way we anticipate the nature of future war today, Force 2025 and Beyond, so too did our predecessors have to plan their research, development, and acquisitions based on projections of enemy capabilities and environments. For America’s senior military and civilian leadership that future was nuclear. They envisioned a world in which conventional ground conflict was obsolete, and the ability to effectively deliver atomic weaponry was the pinnacle of military prowess. The Field Artillery, which had been the force responsible for the greatest number of enemy combatant casualties for both World Wars and the Korean War, had just been usurped from its kingly position… on paper.

From their perspective they had a point. Under the Eisenhower Administration, Massive Retaliation was the established strategy in dealing with future aggressors. The moment a potential enemy began movement towards armed conflict the United States would retaliate with a disproportional amount of force which at this juncture meant nuclear strikes. They further anticipated that potential enemies; i.e. the Soviet Union, would be able to effectively deliver their own upon the battlefield which meant that the United States’ level of retaliation would have to be extremely disproportionate to the point of national-level annihilation. With combatants dropping nuclear weapons throughout the battle space the massed maneuvers of infantry, armor, and airborne divisions would become nothing more than ineffective and expensive targets for destruction.

The newly established Air Force, previously Army Air Corps, and the Navy were the only departments capable of the delivery of nuclear weapons, and were therefore emphasized during defense budget allocations. There would be no need for a robust Army in this type of warfare, and what resulted was a large shift in resources toward the other departments. The post-Korean War Army was in financial dire-straits with many in its leadership questioning its purpose. In an anecdotal incident, from COL Andrew J. Bacevich book The Pentomic Era, an Army officer was quoted jokingly, “ that the Army be absorbed into the Air Force: such a move would save money, reduce inter-Service rivalry, and help the average Soldier’s morale by putting him in a snazzy blue uniform.” Indeed a dark time for the Army!

GEN Matthew B. Ridgway. Photos courtesy of CPT Colin Marcum

GEN Maxwell D. Taylor. Photo courtesy of CPT Colin Marcum

To counter attempts within the DoD to siphon money away GEN Matthew B. Ridgway, as the Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) from 1953 to 1955, facilitated a shift in Army doctrine, organization, training and material while GEN Maxwell D. Taylor; CSA from 1955 to 1959, carried it through to implementation. Their intent was to make this new army irresistible to civilian leadership by creating a fighting force that could fight, survive, and win a ground war during a nuclear conflict. The old organization of the triangular division; where divisions were comprised of three maneuver regiments, was replaced by the pentomic division; being itself comprised of five battle groups. The battle group served a similar purpose as seen previously in the regimental combat team (RCT), and whose modern adaptation we now see in the brigade combat team (BCT). Watch the video:

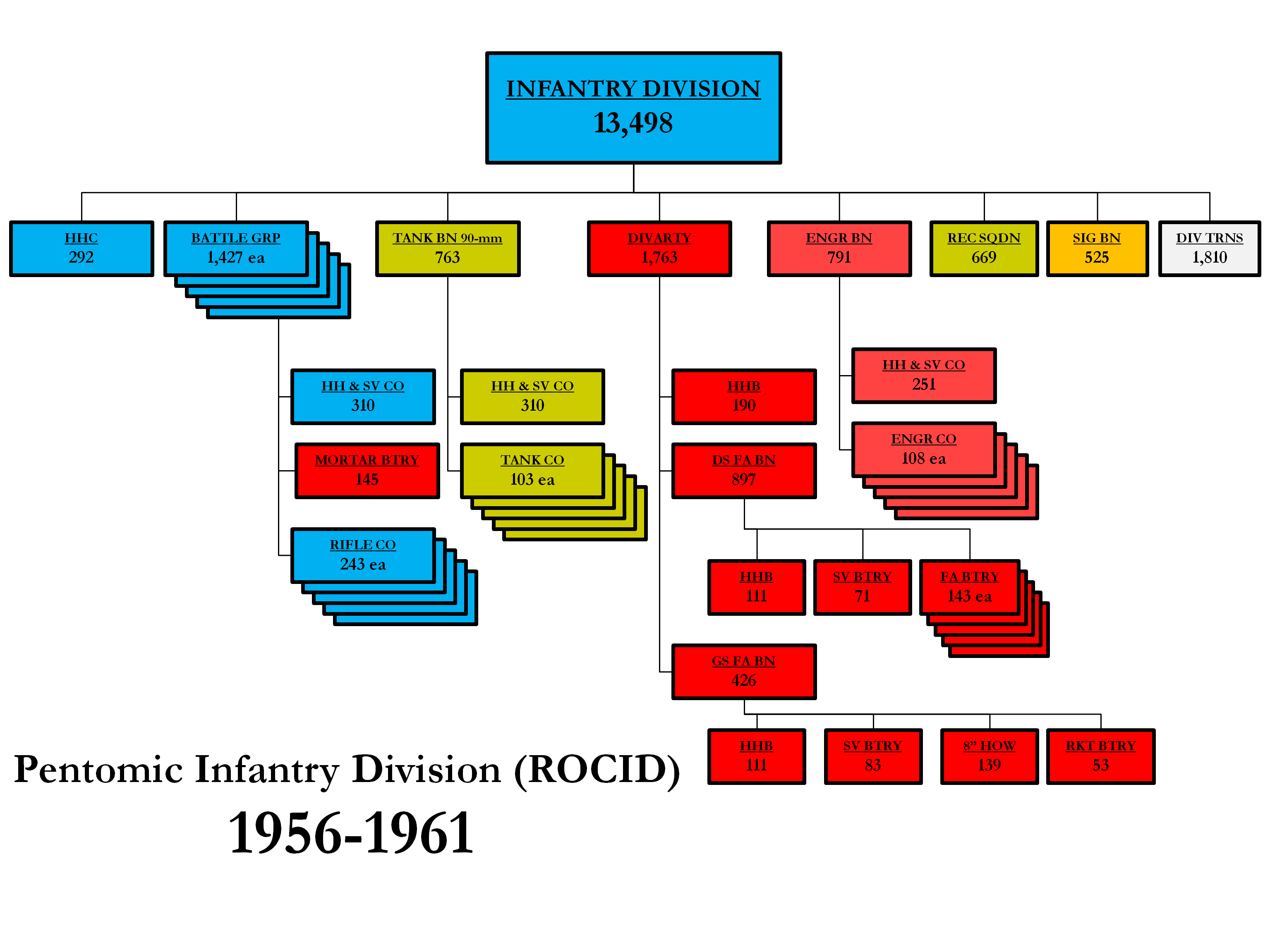

The Reorganization of the Airborne Division (ROTAD) and Combat Infantry Division (ROCID), as they were officially called, provided commanders a lesser number of Soldiers, but greater number of subordinate units. These units would be dispersed throughout the area of operations not amassing combat power in any one particular area. Under this new doctrine a company-sized element had an area of responsibility previously designated for regiments, and for the battle group an area for a corps or numbered army. This concept was possible with three different advancements in military technology.

An example of a ROCID Organization

First, the development of armored personnel carriers and transport helicopters, allowed the battle group to be able to quickly mass combat power for an assault, or in defense against an attack, commit to the engagement, and then quickly disperse before the enemy could counter with nuclear weapons. Second, the use of amplified and networked radio relays throughout the battle space would allow the commander to continue to exercise control of their remaining forces should an atomic detonation destroy nodes within that communication network. Third, the ability to deliver devastating, long-range firepower in the form of big guns, rockets, and missiles with heavy explosive or atomic warheads meant that anywhere within the battle space the battle group could offset its numerical inferiority with superior Fires.

While each division had one composite battalion of five batteries, three towed and two self-propelled, of direct support Field Artillery, the DIVARTY had a composite battalion of an 8-inch (203 mm) towed howitzer battery and an Honest John rocket battery providing general support. The conventional firepower of the four guns and two launchers of the DIVARTY are significant to be sure, but its nuclear capability is what sets it apart from the previous generation. Equipped with atomic warheads this one battalion had the capability to leverage more destructive firepower than all Field Artillery fired during the Second World War.

In combat the DIVARTY served primarily three purposes. First was providing powerful general support Fires for the pentomic division. Second was the employment of the battle groups direct support artillery battalions, and assignment of their tactical missions. Third was the management of the Fires nets by which calls for fire and fire direction were relayed. Furthermore, at the operational level, the DIVARTY acted as a bridge between the artillery liaisons of the battle groups and operational fire support assets available to the corps; including corps and army group artillery, air support, and naval gunfire.

Beyond the tactical fire support provided to the maneuver forces of the battle groups, the ability of the pentomic division's DIVARTY to deconflict Fires at the operational level, was an important requirement for the capabilities of the time. Nuclear weapons’ area of effect was significant, and as a result the dispersion required of conventional fighting forces themselves needed to be expanded. Additionally, the added range afforded by rockets and missiles increased the projection of power available to the Army. Coordination and deconfliction of Fires at the operational level was, therefore, important for ground-based warfare upon a nuclear battlefield. At the maneuver boundaries of a division, the massing of enemy forces or other high-value/high-payoff targets requiring the utilization of atomic firepower could potentially see its effects; blast, heat, and radiation, emanate into an adjacent unit’s battle space.

Photo courtesy of CPT Colin Marcum

The ability of the DIVARTY to coordinate for external Fires was paramount. Even with the long-ranging firepower available to the DIVARTY Field Artillery officers at the time felt that the size and scope of the battle space a pentomic division would have to occupy would be too great. In a situation in which an enemy was conducting a localized attack against a battle group providing nuclear fire support may prove impractical; without causing significant fratricide, requiring the use of conventional munitions. Due to the ranges in which each battle group operates, the ability of their direct support battalions to mass Fires may be limited. What would result is a numerically inferior U.S. maneuver force fighting a numerically superior enemy and receiving potentially limited and ineffective fire support to combat them. Naturally, artillerymen with a recent knowledge of the Korean conflict, and how fire support, at many times, was the only thing preventing our maneuver forces from being overwhelmed by North Korean and Chinese communist forces, would be hesitant backing a doctrine that didn’t allow for the massing of conventional Fires.

While leaders in the Field Artillery had their own concerns about their ability to support maneuver under the pentomic design, the maneuver forces had their own concerns as well. While battalions were retained for the Field Artillery, it was not the same for our maneuver brethren. Due to the nature of the pentomic organization, the battle group, similar to a regimental-level command, was comprised of five company/troop level commands. A young Infantry or Armor captain, after finishing their time as commander of a company/troop, would have to wait until they attain the rank of colonel before they take another command; the battle group. There was concern at the time such a long hiatus from command would atrophy many of previously developed leadership skills. Coupled with the numerous subordinate units of the battle group, having to be command and controlled; five maneuver companies/troops, an artillery battery, and various combat support/ service support companies, it was a daunting challenge for someone of limited experience.

The issues arising from the pentomic design were being voiced, and serious questions were being raised as to its ability to even hold terrain against a conventional aggressor. Again, the purpose for the design was to fight, survive, and win a ground war where the possibility of nuclear weapons may be used; however, if it could not succeed with conventional weapons then it would have to succeed with nuclear ones. This was never the desired end state for the Army, and this concern was initially voiced by Ridgway who viewed the proliferation of nuclear capabilities within the Soviet Union and other future threats as eventually leading to a situation in which the Massive Retaliation national strategy would inherently bring a counter-nuclear strike against the United States and its allies. Eventually, the idea of mutually assured destruction; in which neither side would engage in nuclear warfare for fear of mutual nuclear annihilation, would require belligerents to voluntarily engage in traditional ground wars without the use of nuclear weapons to advance their interests. Therefore, a strong conventional army would still be needed.

For Ridgway and Taylor, the pentomic concept with its dispersed maneuver forces and nuclear armed DIVARTYs was not a desired end state. It was simply a placeholder for the Army to maintain its relevance within a DoD entirely onboard with the allure of nuclear weapons. When President Kennedy took office he understood the realities of mutually assured destruction coming into the American mindset, and changed the national strategy of Massive Retaliation to that of Flexible Response. It called for initial conflict to be carried out conventionally in a Direct Defense against Soviet aggression; followed by a Deliberate Escalation with the use of small tactical nuclear weapons, should conventional means begin to fail, then finally entering into General Nuclear Response against the Soviet Bloc. This meant that a fighting force capable of countering large conventional forces on the ground without the initial use of nuclear weapons would be needed, which resulted in further organizational changes within the Army.

ROTAD and ROCID made way to the Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD) and the return of the maneuver battalions and more manageable battle spaces. The pentomic concept was not a wasted effort; however, because the drive to achieve a revolution in military affairs did result in numerous concepts and technologies that persisted through to today. The deployment of infantry via armored personnel carriers and helicopters quickly across the environment lead to the development of future mechanized and air assault divisions and their tactics, techniques and procedures. The advanced anti-aircraft missile systems; such as the Hawk and Nike series, provided a foundation of capabilities for the anti-aircraft artillerymen to later break away as their own separate branch. Advancements in remotely controlled aircraft to support aerial observation for artillery were the beginning of the unmanned aerial platforms that we see today. In the few years of the reorganization of the Army under the pentomic concept it received a needed boost in technological capital that helped it not only persist through significant budget reduction but through the Vietnam conflict.

In many ways the Army of the 1950’s is similar to the Army of today. After the significant loss of life during the Second World War and Korean War, the prospect of massive retaliation with nuclear weapons alleviated the burden of protecting the United States from that of traditional warfighters to technicians and operators separated from the enemy by great distance. The promise, a quick victory in conflict, or even better a strong deterrent to it would allow the United States to supports its allies and achieve its interests without costly wars. Though the Army was against this pre-occupation with atomic weaponry, it was in a losing fight against the Air Force and Navy for taxpayer dollars. It adapted to that environment with the pentomic concept until the Kennedy administration established the Flexible Response strategy.

Contemporary conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have soured the taste of ground conflict for many Americans, but the United States still seeks to project its power and influence around the globe. After the end of large scale military operations in Iraq and the continued drawdown of forces in Afghanistan, the administration looks as if it desires to relieve the United States of the requisite to commit ground forces to future stability and counter-insurgency operations. Instead they would focus on the development of local capabilities of supportive governing agencies to contribute to their own stability while the United States would assist indirectly with service support and limited air power. While the purpose for this projection of power is inherently in line with our strategic goals: i.e. countering terrorism, securing global commons, etc., the biggest threat to this projection comes in the form of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

As of the beginning of 2014, the acknowledged A2/AD threats were China and Iran and it was juxtaposed to these potential future rivals that the DoD adopt the Air-Sea Battle Concept. If the capability of victory for the United States would be hinged on the ability for the Air Force and Navy to strike at military targets with impunity, then any enemy capability that hindered that ability would need to be countered. The Chinese and Iranians have developed arrays of integrated air defense systems and banks of high-speed anti-ship missile batteries geared towards defeat an enemy’s ability to project power. Utilizing stealth aircraft, long-range missiles, and electronic attack they would defeat command and control nodes, tracking systems, and other critical infrastructure in order to cripple the A2/AD network, opening up the enemy up to a greater variety of means in which to pressure them towards our desired ends.

For the ground-based operations of the Army there are few systems that can provide the level of standoff capabilities available to the Air Force and Navy. To be sure, our redesignated DIVARTYs with their stocks of extended range munitions do provide the Army with the capability to project its power over great distances, but they were never intended as a standoff weapon system. As always the Field Artillery is providing, integrating, and coordinating for Fires in support of maneuver forces. Even long range suppression of enemy air defenses through the use of the Army Tactical Missile System would be in support of friendly aircraft operating in the area. Whereas the Air Force and Navy project power from the air and sea onto the land the Army projects its power from and through the land with maneuver forces which is everything but standoffish. And as a result, with the DoD’s focus on standoff weaponry, much like their previous focus on nuclear capabilities in the 1950s, the Army is left without a significant capability that is now in demand.

(As of Oct. 14, 2014) With the coalition against ISIS underway the United States has committed to an air campaign against their forces. The administration has been understandably reluctant to commit ground forces instead focusing exclusively on the projection of airpower to degrade and defeat their capabilities. Most have acknowledged that some form of ground force will be necessary, but what form that will eventually take is under continuous development. As of right now; however, the standoff capability that the Air Force and Navy provide our military allows us to slowing degrade the ability of ISIS to conduct its operations throughout the region while still providing us the ability to quickly disengage should the diplomatic or political situation deem necessary.

Much to the chagrin of many of the Army’s senior leaders, most vocally GEN Raymond Odierno, as our Chief of Staff of the Army, we are undergoing a significant reduction of our manpower in response to our reduced budget. Our sister services themselves are facing significant budget reductions, but it is being felt most within the Army which had increased in size during the conflict. Attempting to bring the force down to pre-9/11 numbers reflects the concept of limited ground intervention abroad. The Army, with its 450k-420k personnel will continue to provide for the defense of the United States, our NATO allies, and partners in the Pacific, but the ability to simultaneously support the types of contingency operations; like in Afghanistan and Iraq, will be reduced. That means that the Air Force and Navy, with their long-range projection of power, have been given greater emphasis in order to allow the United States to continue to support its interests.

Odierno, along with GEN James Amos and Admiral William McRaven, as leaders of the nation’s landpower forces have stated within the Strategic Landpower White Paper that,

The United States and its Armed Forces once again find themselves at a crossroads. After ten years of war, the Nation is rebalancing its national security strategy to focus on engagement and preventing war. Some in the Defense community interpret this rebalancing to mean that future conflicts can be prevented or won primarily with standoff technologies and weapons. If warfare were merely a contest of technologies, that might be sufficient. However, armed conflict is a clash of interests between or among organized groups, each attempting to impose their will on the opposition. In essence, it is fundamentally a human endeavor in which the context of the conflict is determined by both parties.”Strategic Landpower: Winning the Clash of Wills

The pentomic concept was designed to not only allow Army divisions to accomplish their mission on a nuclear battlefield, but persuade the DoD that it was still relevant. Pentomic divisions had with them DIVARTYs equipped with not only conventional munitions, but nuclear capabilities in order to give the needed firepower strength to these smaller organizations. They offered the United States the ability to continue to fight ground wars while using the technology of the time to make it quicker and less costly on the nation in terms of both money and lives. It offered at the tactical and operational levels of war what the Air Force and Navy were offering at the strategic level; an easier victory. The Army argued that ground wars would still be necessary, however, adopted the pentomic concept to acquiesce to the desire for technological change. The Nuclear DIVARTY, alongside advancements in communications and mobility, provided that change.

Contemporarily the leadership of the Army, Marine Corps, and Special Operations Command has espoused the Strategic Landpower concept in order to sustain relevance for their respective services in the current political and budgetary environment. Now that is not to say that the ROTAD/ROCID and Strategic Landpower will turn out the same way. Strategic Landpower was adopted by our ground-based forces after a realization that operations on the human domain are necessary to achieve our desired ends, and the only way to create lasting effects upon that domain in on the ground, where humans live, not exclusively from the air and sea. As a result, Strategic Landpower should have a more lasting impact, because it is a re-envisioning of the purpose of landpower; whereas, the pentomic design of ROTAD/ROCID was a drastic change to doctrine, organization, training, and material in preference towards atomic weaponry.

Our armed forces are indeed at a crossroads, and our leaders have identified that this not the first time. Reflection upon the history of the United States Armed Force, the Army, and the Fires Force will be necessary to ensure that the course of action that we propose to the DoD is both relevant to the environment in which we find ourselves occupying and that it is able to achieve our nation’s desired ends. While new threats are emerging, testing whether reducing our landpower forces is a viable undertaking at this juncture, we can take to heart that this history that we share has placed our contemporary Army, and its Fires Forces, in a far more manageable position than our predecessors.